So what can an ancient sea port famous for it’s wide variety of migratory birds have to do with one of the deadliest plagues in human history? I suggest avian flu may be the culprit. But first.an overview. We will concentrate on the modern Egyptian port city of Tell El Farama

For the visitor to Tell el-Farama, located in the extreme northwestern Sinai not really very far to the east of Port Said, it might be difficult to image this once being a part of the Nile Delta, but it was in ancient times, with two branches of of the Nile (Ostium Pelusiacum) surrounding what was then Pelusium, the eastern gateway to Egypt. Actually, it occupied the eastern extreme of the Nile Delta, and technically remains in the delta today. The site has been known by many names. It has been called Sena and Per-Amun by the Egyptians, Pelouison by the Greeks, its Aramaic name was Seyan, and it has biblical significance as Sin. The Greek form of the name is derived from the term pelos, which refers to mud or silt, The port is famed for the amazing volume and variety of it’s migratory birds,many coming from China and Africa. The city is also thought to be the first known city to suffer from the Great Plague of Justinian.

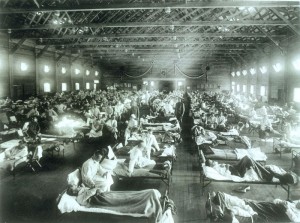

In 541 AD, the Plague of Justinian was first reported and began to spread across the Byzantine Empire. The first place it was reported was,….Pelusium. But let us first look at the sheer magnitude of the Plague of Justinian, a plague that affected the Emperor himself !

The Plague of Justinian (AD 541–542) was a pandemic that afflicted the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire), including its capital Constantinople. It has been claimed as one of the greatest plagues in history. The most commonly accepted cause of the pandemic has been bubonic plague, but recent research suggests that if it was bubonic plague it was of a sort unrelated to both present and medieval plague infections.How odd that nobody seems to have looked at some ancient version of Avian Flu as a possible cause.. The plague’s social and cultural impact during the Justinian period has been compared to that of the Black Death. In the views of some 6th-century Western historians, the plague epidemic was nearly worldwide in scope, striking central and south Asia; North Africa and Arabia;and Europe all the way to Denmark and Ireland. Genetic studies point to China as having been the primary source of the contagion, If this is true, naturally, we have to look beyond the usual suspects, the rats, and turn our attention to the avian centric city port of Pelusium, located along the eastern Nile in Egypt, a city known in the ancient world as a place teeming with hundreds of varieties of migratory birds, Birds, far more than rats, defined the natural eco system of ancient Pelusium. Either way, an estimated 40% of the human population that contacted this horror died. Estimates range up to 25 million fatalities.No single plague defined the sheer scope of a pandemic in ancient times, and it was the last great plague known to have afflicted mankind before the advent of the Black Death in 14th century Europe.

Throughout the Mediterranean basin, until about 750, the plague returned in each generation The waves of disease had a major effect on the future course of European history. Modern historians named this plague incident after the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I, who was in power at the time of the initial outbreak; he contracted the disease himself yet survived.

The outbreak in Constantinople was thought to have been carried to the city by infected rats on grain boats arriving from Egypt.To feed its citizens, the city and outlying communities imported massive amounts of grain—mostly from Egypt. Grain ships may have been the original source of contagion, as the rat (and flea) population in Egypt thrived on feeding from the large granaries maintained by the government. The Byzantine historian Procopius first reported the epidemic in AD 541 from the port of Pelusium, near Suez in Egypt. Two other first-hand reports of the plague’s ravages were by the Syriac church historian John of Ephesus and Evagrius Scholasticus, who was a child in Antioch at the time and later became a church historian. Evagrius was afflicted with the buboes associated with the disease but survived. During the disease’s four returns in his lifetime, he lost his wife, a daughter and her child, other children, most of his servants, and people from his country estate. Now let’s revisit Pelusium, where the epoch of the Great Plague of Justinian began. Can we make an avian connection to the outbreak of Plague? Not in this blog. But it seems reasonable that we start asking some questions in regard to this possibility.

Pelusium was an important city in the eastern extremes of Egypt’s Nile Delta, 30 km to the southeast of the modern Port Said. Alternative names include Sena and Per-Amun (Egyptian, Coptic: Paramoun meaning House or Temple of Amun),Pelousion (Greek, Πηλούσιον), Sin (Chaldaic and Hebrew), Seyân (Aramaic), and Tell el-Farama (modern Egyptian Arabic). Pelusium was the easternmost major city of Lower Egypt, situated upon the easternmost bank of the Nile, the Ostium Pelusiacum, to which it gave its name. It was the Sin of the Hebrew Bible (Ezekiel xxx. 15); and this word, as well as its Egyptian appellation, Peremoun or Peromi, and its Greek (πήλος) connote a city of the ooze or mud (cf. omi, Coptic, “mud”). Pelusium lay between the seaboard and the Deltaic marshes of the Delta, about two and a half miles from the sea. The Ostium Pelusiacum was choked by sand as early as the first century BC, and the coast-line has now advanced far beyond its ancient limits, so that the city, even in the third century AD, was at least four miles from the Mediterranean.

The principal produce of the neighboring lands was flax, and the linum Pelusiacum (Pliny’s Natural History xix. 1. s. 3) was both abundant and of a very fine quality. It was, however, as a border-fortress on the frontier, as the key of Egypt as regarded Syria and the sea, and as a place of great strength, that Pelusium was most remarkable. From its position it was directly exposed to attack by the invaders of Egypt; several important battles were fought under its walls, and it was often besieged and taken.

A titular metropolitan see of Augustamnica Prima in Egypt, mentioned in Ezech., xxx, 15 sq., (A. V. Sin), as the strength or rampart of Egypt against his enemies from Asia, which clearly outlines the eastern frontier of the Delta. Sin in Chaldaic, and Seyân in Aramaic, means mire, like the Greek Pelousion, which is a translation of it; and which, according to Strabo (XVII, i, 21), refers to the mire and the marshes which surrounded the town. The latter was very important, being on the route of the caravans from Africa to Asia, also because its harbor joined the sea to the branch of the Nile called Pelusiac. The Pharaohs put it in a good state of defense. Among its sieges or battles were: the expedition of Nabuchodonosor, 583 B. C.; that of Cambyses who stormed it, 525 B. C. (Herod., III, 10-12); that of Xerxes, 490 B. C., and of Artaxerxes, 460 B. C.; the battle of 373 B. C. between Nectanebus King of Egypt, Pharnabazus, Satrap of Phrygia, and Iphicrates, general of the Athenians. In 333 B. C. the city opened its gates to Alexander; in 173 B. C. Antiochus Epiphanes triumphed under its walls over Ptolemey Philimetor; in 55 B. C. Anthony captured it; and in 31 B. C. Augustus occupied it. The Shah Chosroes took it in A. D. 616, Amru in 640; Baldwin I King of Jerusalem burned it in 1117. The branch of the Nile became choked up and the sea overflowed the region and transformed it into a desert of mud. A hill, covered with ruins of the Roman or Byzantine period and called Tell Farameh, marks the site. There are also the ruins of a fort called Tineh. Through all these silk road battles, the abundance of birds was referred to by contemporary observers

The first known bishop is Callinicus, a partisan of Meletium; Dorotheus assisted at the Council of Nicæa; Marcus, Pancratius, and Ammonius (fourth century); Eusebius (first half of the fifth century); George (sixth century). Pelusium became the metropolitan see of Augustamnica when that province was created, mentioned first in an imperial edict of 342 (Cod. Theod., XII, i, 34). The greatest glory of Pelusium is St. Isidore, died 450. Under the name of Farmah, Pelusium is mentioned in the “Chronicle” of John of Nikiu in the seventh century (ed. Zottenberg, 392, 396, 407, 595).

LE QUIEN, Oriens christianus, II, 531-34; AMÉLINEAU, La géographie de l’Egypte à l’époque copte (Paris, 1893), 317; BOUVY, De sancto Isidoro Pelusiota (Nîmes, 1884). Now we get to the most interesting part of this blog. The Bird factor, as I call it. Contagions academically weighty blog informs us of the following:

Pelusium is an unusual port, located in the swampy delta at least 4 kilometers from the shore of the Mediterranean even in the sixth century. Then it sat on the eastern most branch of the Nile delta; today, it is called Tell el-Farama, separated from the Nile by the Suez Canal 30 km to the west. It was connected to Alexandria and through the Bitter Lakes with the Red Sea port of Clysma (modern Suez) by a network of canals. These canals go back to the time of the pharaohs, rebuilt and renewed under the Romans/Byzantines .The channels depended upon water diverted from the River Nile and therefore relied on the water being high enough in the river to fill the channels. The River Nile was at its lowest depth between March and May. Waters began to rise in June peaking in September . As a secondary port that was not easily accessible from the sea, Pelusium’s trade was primarily food and textiles sent to Gaza and the Levant. Alexandria was reached more slowly via the channels through the delta.

These trade networks, functioning when the waters of the Nile filled the canals, are highlighted by the appearance of plague in that first year. Plague arrived in Pelusium with the rising waters in mid-July 541, traveled east to Gaza by mid-August and reached Alexandria to the west in mid-September 541. It arrived in Alexandria after the yearly grain shipments have left explaining why the plague did not reach Constantinople by sea until April or May of 542 . Incoming traffic to Pelusium came from the Red Sea ports.

Red Sea Traffic

Red Sea traffic was vital because of the slow and difficult movement of goods on the Nile, where traffic was seasonal at best. Strictly by the River Nile from Sudan to the Mediterranean has been estimated at 28 days. Shipping goods into the Red Sea and through the channels of the delta to the Mediterranean should be considerably faster.

In the sixth century, Byzantium and Persia were fighting a proxy trade war in the Red Sea, a key control point on the southern (maritime) branch of the silk/spice road. The Axumites (Ethiopians) worked on behalf of Byzantium, while the Jewish kingdom of Himyria (Yemen) was officially aligned with Persia . Persians controlled the Persian Gulf but not all of the Indian ocean between the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. Christians of Himyria and some Axumites were able to make trading runs to southern India and the island of Ceylon (called Taprovani by Byzantines, modern Sri Lanka), leaving Byzantine coins in Ceylon as evidence of their trade . Axumites brought trade goods to the Byzantine Red Sea port of Berenike and Myos Hormos, the last major port for sea-going vessels. However, by the mid-540s these ports had to be abandoned. Berenike is last recorded in 524-525 . Under pressure, the Byzantine trading ports were pulled back to the Sinai peninsula.

The Levant via Wikipedia Commons.

The plague is first reported at Pelusium, which points toward the ports of Ailana (Aqaba) and Clysma (modern Suez) on the Sinai peninsula . From Ailana goods moved over land to the Levant. Clysma was a difficult port to navigate due to high winds but was made vital by historical events.

The city of Clsyma served as the gateway to the channel leading to Pelusium, and a frontier fort where the Byzantine ambassador to Axum was stationed. Less than ten years before the plague erupted, Duke Aratios retook the trading station on the isle of Iotabe from the Saracens in 534. This island was protected and defended from Clysma.

Although a better military installation than port, the port of Clysma was well-known in the Late Antique world. Gregory of Tours, writing in his Historia Francorum, in the late 6th century mentioned Clysma as a stopping place on the Hebrews flight from Egypt.

“The river about which I have told you flows in from the east and makes its way round towards the western shore of the Red Sea. A lake or arm of water runs from the west away from the Red Sea and then flows eastwards, being about fifty miles long and eighteen miles wide, At the head of the water stands the city of Clysma built there, not because of the fertility of the site, for nothing could be more sterile, but for its harbour. Ships which come from the Indies lie quietly at anchor here because of the fine position of the harbour, and the goods collected here are then distributed all over Egypt.” (Gregory of Tours, I.10, p. 75 )

Clysma was the primary port for trade with “India”, the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Anywhere along the Red Sea or Indian Ocean could be called “India” in ancient sources; Procopius placed the head of the Blue Nile in India, a common mistake for Ethiopia . For our purposes here, India should be thought of as the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. In the 6th century, Clysma would have been a key point in the southern (maritime) silk road from the Far East bringing silk and spices.

Tsiamis, Poulakou-Rebelakou, and Petridou summarize the supporting evidence for Clysma (Suez) as the site of entry for the plague into Egypt with the following facts.

The ports of Berenike and Myos Hormos were abandoned and the Via Hadriana (the road from Bernike to the River Nile) was destroyed in the sixth century. Berenike is last reported in 524-525.

Traffic shifts to an upgraded port and fortress at Clysma, which protects the trading post on the island Iotabe. Clysma kept a fleet of military ships for the protection of the island of Iotabe, used effectively to retake it from the Saracens in 534. It was also the station of a top Byzantine official who served as ambassador to Axum.

Tsiamis, Poulakou-Rebelakou, and Petridou acknowledge that the link between Clysma and Pelusium is not completely secure. Travel along the Bitter Lakes was problematic and the channels relied on water from the Nile to function. Towns in the Sinai were building their own defenses . Like everywhere else along the Roman/Byzantine frontier, they were under attack from tribes from outside the empire and slowly failing. Yet Byzantine efforts to keep an ambassador to Axum and a military presence at Clysma suggests that Red Sea trade was not only still valuable to them but accessible to the Mediterranean ports. Alexandria was still the primary Mediterranean port of Egypt, but Pelusium was closer and more accessible from Clysma, so plague possibly coming via Clysma reached it first.

If we maintain the assumption that plague did not arrive at Pelusium from the Mediterranean, then it is likely that it traveled the Late Antique version of the Suez canal, then a series of channels that linked with the Bitter Lakes between Clysma (Suez) and Pelusium. To look for the origins of the first pandemic we need to look further at the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, and the maritime silk road.

So, in a nutshell, the plague that ended up decimating the Byzantine empire killing hundreds of thousands seemed to have gained it’s first foothold in the Sinai in Egypt before spreading it;s horrors into the bowels of the Justinian empire.And Pelusium, with it’s 200 different varieties of migratory birds, and fertile marsh lands, could have been the petri dish that helped create the first super plague ever recorded in history. Perhaps one day, long after the current Egyptian political uncertainty finally calms down, researchers can have access to this ancient port and investigate what promises to be an exciting chapter in plague history. I once again, hold suspect the suggestion that this plague ( and other’s) were mainly rodent flea based. Once again, we must look closely at some long lost variant of Avian Flu as a possible culprit. Like the bird thick Italian port city of Genoa, linked to the Black Death of the 14th century,the port city of Pelusium, along an important migration route for over 200 varieties of birds, must be examined for possible avian flu links to this long forgotten and poignant chapter in history.

Read More